News

Wild and Wet, SAR hoist training in Nova Scotia

October 11, 2018 By Carroll McCormick

High winds spin the basket stretcher and rescue specialist as he struggles in driving rain to switch from the dead hoist to the backup. Above him, the hoist operator crouches in the doorway of a Sikorsky S-92, buffeted by prop wash. In the water a sodden victim gulps some air and disappears again under two-metre waves.

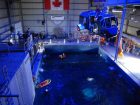

A SAR crew practices a difficult edge transition manoeuver on MAST’s Sikorsky S-92 platform. (Photo by Carroll McCormick)

A SAR crew practices a difficult edge transition manoeuver on MAST’s Sikorsky S-92 platform. (Photo by Carroll McCormick) Finally, the poor soul is captured, pulled aboard and assures the paramedic that he will live to write another day. So went my foray into the new world of synthetic Search & Rescue (SAR) training, conducted at a level of realism (that was not an actual S-92, but a very effective training aid) that leaves certain traditional methods back in the Stone Age where they belong.

My thrash in the deep blue took place in a gigantic building completed in 2014 by Survival Systems Training Limited (SSTL) in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. Called the Marine Aviation Survival Training facility (MAST), it is SSTL’s biggest push to make training involving helicopters and water, from bullying commandos to capsizing submerged choppers full of offshore oil workers, more realistic.

On that day, Total Response Solutions (TRS), a Dartmouth-based helicopter training and service company, was putting a SAR crew, one of several employed by Canadian Helicopters Limited in the service of providing passenger movements and SAR support for a BP Canada drilling project off the coast of Nova Scotia, through quarterly recurrent helicopter rescue hoist training.

TRS has been leasing MAST time for three years now. “Before MAST, it was static training on the shop floor. There was no way to do it in a realistic environment,” says Derek Rogers, a decorated, ex-military SAR specialist and currently the TRS Project Manager. “We literally did it two feet off the floor – a completely unrealistic training scenario.”

Of his company’s push for ever more realistic training since it began in 1998, SSTL owner John Swain notes, “It would be better to have no training rather than negative [incorrect] training, because it sets up a schema in the brain that would condemn you to failure. It [is] very, very important to have people repeat and repeat the correct actions.”

The hoist training takes place in a configured S-92 platform (think: full-size mock-up of a S-92 fuselage), which ordinarily functions as an egress trainer for helicopter ditching courses. But with the rotate (capsize) function used for egress training disabled, and the aft fuselage fitted with extras like Breeze Eastern hoist, hoist control panel, manual and automatic cable cutters, standard crew hard points, plus two externally mounted fans to stir up some rotor wash, the egress trainer becomes the Hoist Emergency Response Training Program, or HERT Locker.

It is not hard to call the HERT a simulator, but Rogers avoids the term simulated environment in favour of synthetic environment. “We don’t want to say simulator, because most people associate simulator with [computer-generated] virtual reality,” he explains. The HERT shell is vaguely analogous to a cockpit simulator, but they part ways in the presentation of the training program and VR cannot replicate what HERT and the MAST can do. “You can’t do VR for the high-angle rescue components of the SAR work, mainly the edge transition, along with the equipment dispatch and recovery in extreme conditions. You need a synthetic environment,” Rogers says.

Take a seemingly straightforward task like lighting a flare under duress. “We always trained guys on a dry dock or in flat water to use a flare. It is not that easy in two-metre seas. You have to get it up out of the water. You have to activate it without burning your hands,” Rogers explains. Or take cable cutting, for example. Rogers notes there was never any decent way to practice that before MAST opened. “No – not with a fall at a height to practice impact positions and full environmental effects.” The HERT platform also allows for realistic training in various other hoist scenarios, including irregular events such as swings and spins, hoist stoppages such as cable fouling, overheating, power failures and cable snags. “None of this can be effectively trained in a static environment.”

Overall, Rogers says, “Safe training practices for winds and sea state limit us from exposing guys to the real rough stuff. For many guys, the first exposure they get to two-metre waves and 100-kilometre winds is in a hurricane… Some guys, depending on postings and scheduling, can go a decade or more before being exposed to these types of conditions operationally.”

As well as giving recurrent training, TRS also evaluates procedures in the MAST. Take, for example, the dual hoist changeover, where a rescue specialist switches from a failed primary hoist to a backup hoist. Rogers tells the story: “Dual hoist changeovers have been discussed and utilized since we went to dual hoist helicopters in the early 2000s. However, we’ve never been able to do them in realistic conditions. The advanced MAST/HERT program has highlighted several issues that were not fully anticipated.

“One [issue] for sure is that, for cable fouling, hoist personnel need to be trained to identify and clear the fouling before attempting the hoist transfer. We have also established that a dual changeover should be a last resort. Everyone thought of it as a primary go-to, but it’s not.”

And do these grizzled SAR specialists – ex-military veterans with decades of experience – find the MAST training worthwhile? Rogers says, “It’s a great way to hone skills. For guys who have had limited exposure, due to postings, etcetera, it’s a great stress inoculation for the real thing. You can do 30 to 40 hoists in an afternoon. You’d take 10 flights to do that many. The guys like the saturation training and being well prepared.”